For those who want a change from the Gospel

2 before Lent – Psalm 104

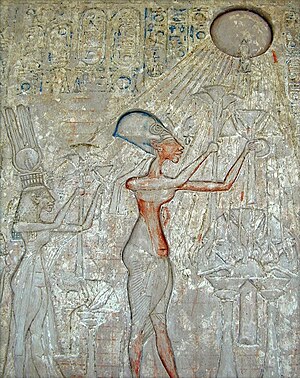

Today’s Psalm passage comes from one of the longer Psalms, 104, and as usual I want to take a look at the whole thing, not just the odd verses plucked, somewhat illogically, from the end of it in our lectionary. The first thing to note about the Psalm is that it looks like a piece of plagiarism! We have a poem which was found in the tomb of Egyptian Pharaoh Ay, who ruled briefly in the 14th Century BC. It is usually thought to have been written by predecessor Pharaoh Akhenaten who began his reign around the 1350s BC. Akhenaten was a great religious reformer, and he championed the worship of the sun-god Aten. The poem, called ‘The Great Hymn of Aten’ is a hymn of praise to him, and this photo, taken at the time, shows him and his family worshipping the sun.

The text shows such a striking resemblance to Psalm 104 that they cannot possibly be unrelated. There is also a close link with the first account of creation, in Genesis 1.

This raises interesting questions about the relationship between these two poems. The Psalm is usually classified as a Nature Psalm, or Hymn to God the Creator, and although we don’t really know when or by whom it was written, it is not impossible that it came from David himself, and therefore quite early in the big story of Israelite worship. If that is so then the Gen 1 account of creation could well be dependent on it, and it might be the case that both of them drew inspiration from the Egyptian poem, but replacing Aten with Yahweh. After all the Genesis 1 story does the same thing with a Babylonian creation story called the Enuma Elish which is at least 1500 years older than the Hymn to Aten. The biblical writers, of course, insist that it was Yahweh, not Marduk, who cut the sea monster in half and created heaven and earth from the two bits. So we needn’t be worried by our faith borrowing or recasting ideas from other faiths or myths: it goes on all the time. We all know, for example, what is meant by Pandora’s box, and the story tells us an important truth without requiring us to believe in Pandora.

So what does this Psalm tell us about God the creator? It begins as the psalmist calls himself to praise in the common phrase ‘Praise the Lord, my soul’. Sometimes we need to remind ourselves to bow before the majesty of God, and much of our hymnody does this job: Praise, my soul, the King of Heaven is perhaps the best example. But the Psalm moves on address God personally, and in particular his power as the founder of the world, in terms which we have said reflect Gen 1. The different species he creates are listed, and then as we come to our fragment we are reminded not just that God created, but also that he sustains what he has made. All creation is nurtured from the hand of God, and the terrible picture of what would happen if he hid and refused this nurture are described. In him is the power to renew or to destroy.

The final verses express the praise of the worshipper, a commitment to praise and rejoice all his life, and a final curse on those who disobey him, or refuse to join in with the worship. Like a closing bracket round the whole Psalm, he calls himself back to praise.

Whilst the literary origins of the Psalm are interesting, I was particularly struck, this time I read it, by the Psalmist’s need to call himself to praise, not once but twice. Indeed there is ample reason for gratitude to God spelt out in the Psalm and evident in the beauty of the world around us, but still it seems that he has to remind himself to be thankful. I can remember going with my vicar when I was a curate to an ecumenical prayer meeting with, among others, a bunch of New Church leaders. As soon as someone said ‘Let’s pray’ they were off, with shouts of praise, muttered ‘Hallelujahs’ and speaking in tongues, while we Anglicans sat quietly waiting for our turn to articulate a prayer. I said to my boss afterwards ‘They’re so emotional, aren’t they?’ to which his reply was ‘No, we’re emotional; they’re committed!’. We were sitting quietly waiting to feel moved into some kind of prayer, while they were going to pray come what may. That kind of commitment to give thanks to God, and even to live lives of gratitude 24/7, is something which the Psalmist recognised, and as a liturgist (one who writes wors for others to use) he encourages us all to remember who God is, what he has done, and what he is doing among us now. And as Christians we’d also want to praise with thanksgiving for what we know he is going to do in the future in the new creation.